Thank You

Notes

I’ve never been very good at writing thank you notes. I don’t have

an acceptable excuse for this shortcoming; I simply forget to take the time to

formally acknowledge my gratitude. I’ve been working on this for a while now,

and I’m getting better. At this time of the year, I’m especially mindful of the

need to thank teachers for all the wonderful things you do each day.

Thank you for the time you spend—during the school day and

frequently beyond—preparing lessons, grading papers, meeting with parents,

learning new things professionally, and attending extracurricular activities.

Thank you for making your classroom a student-centered environment

where the kids do the thinking and the talking, even when it would be easier

and faster just to tell them what you know yourself.

Thank you for taking risks with technology because you know that

students in today’s world engage actively when you let them connect online.

Thank you for believing in your students. You may be the only one

in their lives who does.

Thank you for having high expectations for yourself and your

students.

Thank you, also, for being flexible and merciful. They are, after

all, kids, and kids make mistakes and do stupid things sometimes. It’s part of

growing up.

Thank you for spending time teaching your students the “hidden

curriculum” of school. Thanks for realizing that there may not be someone at

home who knows how to navigate the world of education and that your guidance

can help someone sail farther than they would have ever anticipated.

Thank you for making your classroom a safe space for students to

struggle.

Thank you for bringing joy to your classroom because a classroom

without joy is a dreary place to try to learn.

Thank you for understanding that not all students learn in the

same way. Thanks for incorporating WICOR (Writing, Inquiry, Collaboration,

Organization, and Reading) into your lessons so that all students have the

opportunity to grow in vital learning realms and to strengthen skills in areas

of weakness.

Thank

you for taking time to pause and let your students reflect on their learning.

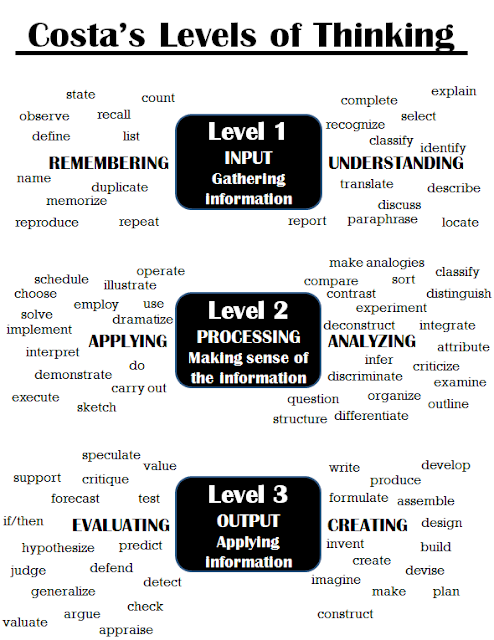

Thank you for realizing that rigor doesn’t mean more work or more

punitive grading; it means work at a higher cognitive level.

Thank you for praising your students, even when it’s hard to find

something to praise.

Thank you for adopting a growth mindset in your classroom and for

helping your students develop one.

Thank you for having a sense of humor. It makes the day more

pleasant for you, for your students, and for your co-workers.

Speaking of your co-workers, thanks for being a team player.

Teaching is hard work, but it’s not a competition. There’s no reason each of us

needs to do all the work ourselves.

Thank you for being vulnerable, for apologizing when you make a

mistake, for admitting you’re not perfect, and for letting your students know

that it’s better to take a risk and fail than not to try at all.

Thank you for viewing assessment as an opportunity for learning,

not as an endpoint, a punishment, a “gotcha,” or a means for sorting or ranking

students. Thanks for realizing that the most important assessment is daily

formative assessment and may alter the path of your instruction.

Thank you for making good use of your students’ time. Having a

well-planned class each day and only thoughtful, meaningful, necessary work

outside of class shows them you value their time and aren’t intending to waste

it.

Thank you for keeping up-to-date professionally. Thanks for

realizing that we can’t keep teaching the same way because it worked in the

past. Times are changing. Students are changing. Our school populations may be

changing. We should be changing in response.

Thanks for being a reflective practitioner, for constantly asking

yourself how a lesson or assignment went and how it can be better next time.

Thank you for asking questions and seeking help when you need it.

Thank you for taking time for yourself to recharge. I hope you

find more of that time over the holidays.

Have a wonderful, restful, and well-deserved break. I am thankful

for the work you do.